I’m sure many of you share my experience of never having read some books that have been so widely talked about that one feels no urgency about reading them. This was long my case with George Orwell’s 1984, which has penetrated our cultural vocabulary unlike any other literary work since Shakespeare.

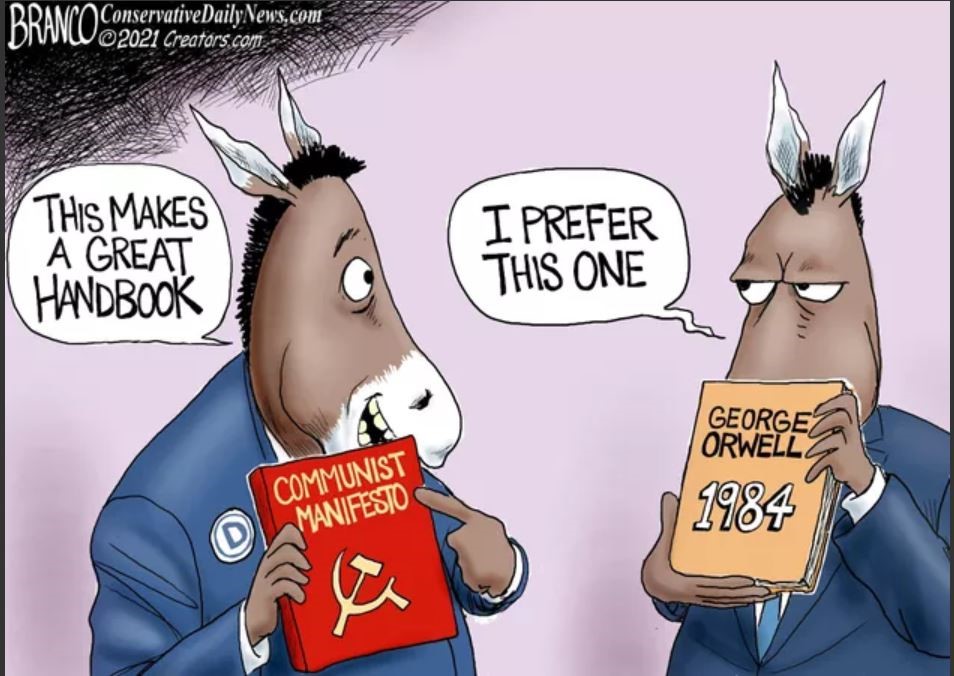

That the current political situation might inspire a reading of 1984 is hardly surprising, given the disquieting similarities between Orwell’s Soviet-inspired dystopia and the woke “socialism” currently installing itself over here. While the ubiquitous two-way screens are certainly prophetic of the kind of surveillance exercised in China, although not yet in the US, the Newspeak of today is if anything more sinister than a language that seeks to make forbidden thoughts “unthinkable” by drastically reducing the vocabulary. Instead of the novel’s wasteful procedure of changing all documents to reflect the Party’s latest version of the “truth,” it is much simpler to reread all past documents, from literary masterpieces to law codes, as embodying implicit inequities whose evil has only now been recognized. Whence the House’s decision to eliminate words like “father” and “mother” from its vocabulary, while others replace breastfeeding by chestfeeding and allow those filling out forms to choose their own “pronouns.”

The most striking difference between our own version of 1984 and the world of Big Brother (and of China) is the absence of any charismatic central figure, and consequently of any but the most hollow gestures of national cohesion. It is inconceivable that any previous society has ever so insistently tolerated and more than tacitly encouraged defining virtue as disloyalty to its national—and civilizational—traditions.

Washington, even Lincoln, no one is sacred, and although blackness is at a premium, no Martin Luther King is being promoted to replace them. Instead, wokeness allows only powerless “victims” to become objects of admiration, while viewing powerful central figures, as exemplified by Donald Trump, exclusively as targets of hostility.

1984 has the figure of Goldstein, obviously modeled on Trotsky, who provides the society with a daily Two Minutes Hate, as well as a yearly Hate Week. But Goldstein/Trotsky is a focus of hate only in contrast to Big Brother/Stalin, whose demand for universal love is satisfied in the book’s final lines, referring to its protagonist, Winston Smith: “He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.” Today there is no Big Brother to love, and except for Hating the Haters, “hate,” along with “resentment,” are terms never attributed to the woke. Countless headlines use these words in connection with Trump and his allies, never the Democrats, just as the weaponless Capitol incursion was an “insurrection” and the riots all summer long, “essentially” peaceful demonstrations demanding “justice.”

In reality, Trump’s sometimes crude put-downs have often been in bad taste, but never hateful; Trump is a mocker, not a hater. One can only hate something that gets under one’s skin, and Trump’s political invective is a means of getting under the other fellow’s skin. The first presidential debate is a good example; Trump mocked Biden, while Biden muttered several expressions of unalloyed hostility, of which I remember in particular racist and clown.

The total domination of 1984 society by the Party obviously has much in common with that of the CCP. But China’s resemblance to Oceania in matters of governance adds an important element that the Soviets claimed but never achieved: economic dynamism. China may fudge its statistics, but “Spengler” (David P. Goldman), who is highly knowledgeable about the Chinese economy as well as its military and technological development, sees China as already a viable competitor with the US in all the areas in which breakthroughs can be expected: AI, quantum computing, space war technology… Tom Friedman has recently expressed his impatience with America’s lack of seriousness in handling this competition (see https://www.mediaite.com/news/ny-times-tom-friedman-tells-chris-cuomo-china-is-doing-better-than-america-despite-bad-stuff-with-the-uighurs/ ).

Thus whereas the overall picture of Oceania, and presumably of the other two empires into which the world is divided, is one of political oppression but also of economic stagnation, with luxuries reserved for the Party elite and, as in the old USSR and in Putin’s Russia as well, no signs of general prosperity or advanced consumer goods, such a picture cannot be drawn of post-Mao China.

As we discover midway through the novel, Goldstein’s “clandestine” Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism explains this stagnation as resulting from a deliberate plan to carry on low-level permanent war among the three states in order to use up the extra productive capacity that would have risked undermining the hierarchical relation between the three “classes” of Inner and Outer Party and the Proles.

This aspect of the novel’s futurism is clearly obsolete. Orwell could not have imagined today’s progressive digitalization, which allows the elites in advanced societies to control vast fortunes while granting a high standard of living to all but the poorest. Although Xi may resemble Big Brother in more ways than one, China has certainly shown itself capable of generating general prosperity, and I have no more faith in the dire predictions of its economy’s collapse than in the rosy hopes, still presumably entertained by a fraction of the Democrats, of its smooth integration within the world of “late capitalism.”

The one advantageous feature of the negative focus of wokeism, as opposed to the insistently affirmative thrust of the cult of Big Brother, is that it allows for a certain distance between intimate and socially marked relations. No doubt the latter have expanded greatly in the cancel culture at the expense of informal person to person contacts, but these still have a good deal of wiggle room in comparison to 1984—and no doubt to today’s China. If the outrageously disrespectful treatment of Trump by our so-called elite has its silver lining, it is that being able to curse the President reflects a far freer society than one where such a thing is unthinkable.

Hence the whole last part of 1984, where the “Ministry of Love” punitively reeducates Smith to not simply accept but believe the Party’s ever-changing version of the Truth, is largely irrelevant to the woke world. We don’t need to terrify people via “Room 101” into accepting that 2+2=5. We merely have to persuade them that 2+2=4 is “white”—or for that matter that mathematics itself, along with correct spelling and grammar, are instruments of “white privilege” (see Chronicle 562). Nor do we have to threaten having your face eaten by a rat—the climax of the novel—to make you betray the love of your life. There is no Big Brother to be jealous of other loves; it is perfectly fine to share your wokeness with as many others as possible. Wokeness is not coercive but persuasive; as I have shown (see Chronicle 684), its “anti-racism” is an extension of the moral equality we all share, the “PC” that prevents us from making disobliging statements about other participants in an ongoing conversation.

As a consequence, the civility untainted by wokeness of most human interactions in the US and other Western-style nations makes everyday life, even in the COVID world of masks and distancing, a welcome oasis in an ever more desertlike public scene. This remains for the moment the West’s most reassuring contrast with the world of 1984.

Acephalous wokeism is unique among political movements in not dictating any positive conduct, even as it winks at acts of anarchy and petty criminality. The metaphoric basis of wokeness is a state of enhanced awareness, not of action: it is a critical rather than a programmatic vision. Hostile to traditional American patriotism, it has no “Pledge of Allegiance” of its own, nothing but a few slogans. Its best known organized element, Black Lives Matter, is nothing but a slogan—one we must take as a credo, rejecting “All Lives Matter” as an impiety. “We Shall Overcome” was far more purposeful than anything one hears today.

The woke program is directed not at building a new society but at enforcing an ever more “critical” attitude toward racism and other forms of alleged victimage, including in particular those that “victimize” the planet and its climate. Whereas the virulent chauvinism of 1984, catalyzed by the pseudo-wars with twin rivals Eurasia and EastAsia, demands that Oceania be seen as a utopia, the woke define utopia only by the negation of traditional (“white”) values. Aside from “greenness,” the new “socialism” has no substance other than the provision of free services. Its sidelining of Bernie Sanders—although he now chairs the Senate Budget Committee—is part and parcel of its focus on identity politics rather than economics.

The different natures of the two social orders are perhaps most clearly seen in the similarities and divergences of their vision of what the novel calls “thoughtcrime.” In 1984, this category is an exaggerated form of the thought control practiced in the USSR, with its newspaper “Truth” (Pravda).

In contrast, in today’s West, the “white” population is increasingly obliged, and often “reeducated,” to understand itself as implicitly guilty of “white privilege,” even as it denounces racism most emphatically. There is in woke society no stable set of values that the majority can profess that would allow it to be in harmony with the social ideal. Its only proper role is lifelong penance for its indelible original sin of whiteness.

But in recompense, the unfailing expression of woke attitudes will allow whites, with certain set-asides for “disparate impact,” to maintain their privileges, particularly if they are active in denouncing those who fail to manifest these attitudes. One of the effects of this social pressure on conservatives is that, even if they refuse to feel guilt for their “privilege,” they tend to be highly vulnerable to any suggestion that they share Trump’s insensitivity to political correctness. Indeed, the never-Trump Republicans condemn him with a disdainful contempt that often exceeds that of the Democrats.

It is easy to mock the absurdities of wokeism, particularly when it ventures into the spheres of political theory or literary criticism. Yet we should not let the abjectness of its intellectual content prevent us from realizing that wokeism could not have taken over the vast majority of the nation’s major institutions, from universities and elementary schools to corporate offices, unless it were indeed the ideology most hospitable to the power elite and its allies in the digital age. And this being true, it may well maintain itself indefinitely.

In fact, by tacitly accepting the West’s and particularly America’s retreat from world leadership, wokeism may even arguably be said to inspire more rational policies than Trump’s America-Firstism. For the latter demands, from not just “flyover country” but the near-totality of the American population, a solidarity and love of country that no longer exists today, and that it is not easy to see reemerging even in a major crisis. The patriotism that emerged victorious from WWII has been in retreat since the Reagan administration, all the more so since George W. Bush’s optimism about our attractiveness as a model for the world proved to have been unwarranted.

Perhaps, in other words, we will be obliged to accept that the relative freedom of social relations in our society as compared to that of China must be paid for by a loss of world leadership, and consequently, by the spread of an ideology that explains this decline as punishment for our victimary sins against our human “others” as well as nature itself. No doubt the Chinese themselves are far more egregious sinners in these areas, but their sins and souls are not our concern. Their resentful experience of a century of Western hegemony, of which Hong Kong was until recently a persistent reminder, makes them willing and able to assert themselves in ways we no longer find possible. Thus it is not altogether unreasonable to claim that, unable to battle them for supremacy, we will do better to modestly hasten our decline by fetishizing “diversity and inclusion” at the expense of the promotion of excellence.

The time may not be far distant when the 1984 dystopia begins to take on for us a nostalgic appeal. Oceania was assured of its position as one of the three mega-states that would continue to rule the world, and Big Brother deserved Smith’s love for this, at any rate.

Whereas it becomes less clear every day whether liberal democracy has the capacity to emerge from its present state of crisis. The banner of White Guilt has been carried from triumph to triumph, in Europe as well as the US. A society that, as we saw quite recently in San Francisco, is proud to remove the names of its founding fathers from its schools can hardly long expect to maintain world leadership.

It is no doubt too soon to resign ourselves to despair. But the reign of the epistemology of resentment, aka “cultural Marxism,” while arousing a great deal of dismay and indignation, has yet to encounter an intellectual opposition that does more than refer to theories that the woke have already rejected.

In contrast, it is clear to me and, no doubt, to a few of my readers that the anthropology based on the originary hypothesis is capable of offering such an opposition. But just as quality and influence have largely parted in the traditional arts, the world of the intellect can no longer be trusted to pay attention to a new way of thinking that seeks to understand the human past in terms of our origin rather than to awoken us to its inequities.

Those of us who are persuaded by this way of thinking can do no more than make every effort to bring it to the world’s attention. At the very least, loving Big Brother is not an option.