theludwigs@comhem.se

The film My Night at Maud’s is the third installment by Éric Rohmer in his 6-part Moral Tales series—one of his most popular films, made in 1969. It takes place in Clermont-Ferrand, the birthplace of Blaise Pascal, between Sunday, the 20th of December, and Sunday, the 27th of December.

Like many of Rohmer’s films, this film is about a moral choice that its protagonist is facing. The protagonist of the film is an engineer, Jean-Louis, played by Jean-Louis Trintignant, who moves to Clermont-Ferrand to take a job with Michelin after living for a long time in Canada and South America. He is both a devout Catholic and an amateur mathematician, who works with probability problems in his spare time. His dilemma is whether he can remain faithful to Françoise, a beautiful young woman whom he notices on the last Sunday of Advent, at mass.

Françoise, whose name he does not know yet, is standing next to him in church in an early scene of the film. After the mass, he tries to follow her, but is unsuccessful—she disappears on her scooter. He becomes obsessed with meeting her again and starts searching for her everywhere in Clermont-Ferrand. The next day he sees her passing him, on her scooter again, and has an epiphanic moment. The voice-over comments that “On that Monday, December the 21st, I suddenly knew, without a doubt, that Françoise would be my wife .”

Later he runs into an old school friend, Vidal (played by Antoine Vitez), whom he hasn’t seen in many years. Vidal is now a philosophy professor at the local university. At Vidal’s instigation, they attend a concert. Jean-Louis agrees to come along because he hopes to meet Françoise (after Vidal tells him that pretty college girls attend these events). Then they go to midnight mass, this time at Jean-Louis’s suggestion. But Jean-Louis does not meet Françoise on either of these occasions. Finally, his friend invites him to visit a female friend of his, Maud, a recently divorced doctor. Jean-Louis is forewarned that she is a very beautiful, smart, and interesting woman, and that Vidal and she have had a brief affair, but things have not worked out. The three have dinner at Maud’s place.

The atmosphere during the dinner is charged with sexual tension. It is obvious that both Vidal and Jean-Louis are attracted to Maud. The conversation turns to religion. Jean-Louis affirms his commitment to Catholicism, saying that he has not been chaste in the past, but neither has he been promiscuous, insofar that he has only had a few long-term relationships. He says that he is not a saint. But he will no longer succumb to temptation, because he is now converted and wants to meet and marry a Catholic woman. Vidal and Maud, who are both atheists and sexually liberated, start teasing him by saying that he must have already met this woman, because he has a dreamy look, as if he is already in love. Jean-Louis vehemently denies it.

When it starts snowing, Maud begs Jean-Louis to stay, saying that it is too dangerous to drive to his distant suburb of Seyrat. Vidal leaves, and the protagonist ends up staying the night. The key moment of the film is the moment of temptation. It turns out that Maud does not have the spare bedroom she has promised him. He first tries to sleep in her armchair, then, at her invitation, lies down next to her in bed. At one point, it appears as if something is going to happen between the two, but he resists the temptation, pushing her away.

The same morning he accidentally runs into Françoise and introduces himself, asking for a date to go to church on Sunday. The rest of the day, is spent with Maud, Vidal, and Vidal’s female friend. In a typical Rohmerian moment of moral ambiguity, Jean-Louis is shown flirting with Maud in a physically affectionate way and even kissing her, which makes his earlier act of renunciation less convincing. On his way home, he runs into Françoise again, and, ironically, ends up spending the night this time in one of the spare bedrooms of Françoise’s student house. She offers the spare room after he has given her a ride home, because his car gets skids and gets stuck on an ice patch. The situation is ironically reversed now. She seems to think that he wants to seduce her, as he walks into her room late at night, looking for matches. But that is not his intention.

After this night, when Jean-Louis and Françoise start dating, he accidentally finds out that before she became his girlfriend, she had been the mistress of Maud’s husband. This means that she is not a perfect Catholic virgin he thought she was. It is Françoise herself who tells him she had had a lover who had broken up with her. He figures out who the lover was.

Five years later, the protagonist and Françoise are married and have a young son. They accidentally run into Maud in a seaside resort. Françoise is tense, expecting him to reveal his knowledge of the affair. He withholds it and tells her instead that Maud had been his last fling before he met her, making it sound as if they had been lovers. In this ultimate gesture of generosity toward his wife, he attempts to make her feel better about her own sin by presenting himself to be a bigger sinner than he really is. Perhaps this is the real moral choice that he ends up making, which is more important than the earlier one of resisting temptation.

This storyline is punctuated by the subtext of the philosophical debate about religion, resolution, temptation, luck, and, ultimately, the nature of faith. Most of the action in the film is constituted by conversations on philosophical topics. The central theme of these discussions is, in one way or another, the problem of choice. Jean-Louis’s imaginary counterpart is Blaise Pascal, known for his ascetic ways and the wager problem that he formulated. The wager refers to Pascal’s argument for believing in God.

The argument takes the form of what in modern philosophy is called game theory. According to its pragmatic logic, we should wager that God exists because it is the best bet. If God does exist and you have bet on his existence (“betting on his existence” needs to be interpreted further: does it imply the mental state of faith or the choice to lead a Christian life?), you have won the lottery, that of an eternal life in Paradise. Another possibility is that God does not exist, but you have bet on his existence. You still lead a Christian life but do not get any reward in the end. In this case, you have not lost anything other than forgone possibly pleasurable but sinful experiences. Following the same logic, if God does not exist, and you have indeed bet on his non-existence, you would not have lost anything because there is nothing you would have done differently. However, if God does exist, but you have bet on his non-existence, that is to say you have led a sinful and unrepentant life, you have lost your very soul: you have lost everything. You are now sentenced to an eternal life of hell and damnation. From the point of view of game theory, which uses the logic of mathematical expectation or expected utility, it makes the most sense to err on the side of God than otherwise. The win, in the case you wager on God, is positive infinity. The loss, in the case of wagering against God, is negative infinity. The first choice is only rational.

(http://james-a-watkins.hubpages.com/hub/Brief-Biography-of-Blaise-Pascal)

The idea of wagering involves both calculation and contract—the former because you need to know the chances and mathematical expectations of various outcomes before you bet, and the latter because you need to ensure your wager’s binding nature. In the end, it must be honored by all participating sides, necessitating some kind of a presiding authority. Significantly, the themes of betting, statistical analysis, and moral accounting are foregrounded in the film. For example, one of Jean-Louis’s hobbies is mathematics, especially statistics. We see him at home, working on mathematical problems (involving the Pascalian binomial distribution and the calculation of mathematical expectation, according to the close-up of the pages). We also find him in a bookstore, leafing through books on statistics and theory of probability.

Importantly also, the idea of Pascal’s wager has a concrete embodiment in Lean-Louis’s moral dilemma. After he first encounters Françoise, it is suggested (but not spelled out directly) that he makes a kind of wager with God (or forces of fate). He decides to stay faithful to her, even though it is very uncertain, at this point, that he might ever meet her again, let alone marry her. The reward in this bargain, presumably, is having the clear conscience of celibate integrity when he hopefully gives himself to her later. The irony of the situation is, of course, that Françoise, having just emerged from an affair with a married man, is not a pure Catholic virgin he has supposed her to be. But Jean-Louis turns this situation into another kind of transaction, telling Françoise that he is glad that she is not a virgin. Since he is not a virgin either, this makes them even.

When he meets Vidal in a café for the first time in many years, he tells him that he likes to dabble in mathematics in his spare time. Statistics, of course, is central to the theme of Pascal’s wager, insofar as the latter is mathematically transcribable in a game-theory matrix of payoffs. But not only that. Vidal suggests that Pascal’s wager can and should be generalized as a philosophical problem, applicable to other areas of life—even for a Marxist like himself. As a Marxist, concerned with social justice and the transformation of society, he needs to believe that history has meaning, otherwise his life’s project becomes meaningless. He must choose between two hypotheses—one that society and politics are meaningless, and the other that history has meaning. Personally, he explains, the former makes much more sense to him. He ascribes to it the probability of 80%. Yet he must stake his life on the less probable hypothesis to justify his actions and choices, because the gain, to him, is infinite.

But does the very idea of “wagering on God” present a conundrum? A belief that we are free to make choices, such as a choice against sinning or a choice to lead a moral life, implies a voluntarist perspective—a worldview that says that we are masters of our actions—which is a position not completely compatible with Pascal’s Jansenism. Jansenism was a religious movement during Pascal’s lifetime, originated by Cornelius Jansen, a Dutch theologian, which was later condemned as a heresy. Pascal subscribed to its tenets and is commonly viewed as a Jansenist. The adherents to this movement advocated a theology quite similar to Calvinism in several important respects. Among other things, they believed in a form of predestination and irresistible grace, which went together with their view of the total depravity of human nature. It is only divine grace that enables human beings to act morally: on their own, they cannot make morally-sanctioned choices. Jansenism was a semi-Protestant movement within Catholicism, insofar as its doctrine did not sanction belief in salvation through works and thus disavowed free will.

Thus, on the one hand, we have Pascal advocating the doctrine of predestination and irresistible grace, which precludes free choice. On the other, we have him promoting a wager, which is a voluntarist act involving choice and free will. A question suggests itself: can we choose to believe in God? The very precondition of Pascal’s wager as a contract stipulates faith. We wager with God on God’s existence, while holding God as the underwriter of our transaction, which is problematic. It is also problematic to assign probabilities to the existence vs nonexistence of God, which would be assigning probability to hypotheticals. According to Jean-Louis, who thinks that Pascal’s wager is too mercantile (“what I don’t like about Pascal’s wager is its calculated exchange”), it only works if the probability of salvation is more than zero. It can be infinitesimally small, but it cannot be zero, because zero multiplied by any number is zero. But since an atheist cannot allow even the slightest possibility of God’s existence, the wager is not valid for him.

But what if one believes that the possibility of God’s existence is more than zero? Is it then possible to choose faith as a state of mind? Or is the wager based on nothing more than the rationality of “calculated exchange”? Pascal seems to think faith is sure to follow. And the portal through which it will enter is simple: imitation. He therefore enjoins his reader in the Pensees to abandon reason and start performing rituals unthinkingly. As you start with mechanical actions, according to him, your thoughts will eventually follow, forming mental habits and gradually leading you to faith. Thus, in a bookstore, Jean-Louis opens Pascal’s Pensées and reads:

You would like to attain faith, and do not know the way; you would like to cure yourself of unbelief, and ask the remedy for it. Learn of those who have been bound like you, and who now stake all their possessions. These are people who know the way which you would follow, and who are cured of an ill of which you would be cured. Follow the way by which they began; by acting as if they believed, taking the holy water, having masses said, etc. (gutenberg.org)

Another question is whether we are capable of the very act of deliberate choice, that is to say of mastery over ourselves? It is not accidental that predestinarian doctrines also stress the underlying depravity of human nature. Can I choose to leave behind my sinful behavior and bad habits? According to Calvinism and Jansenism, human beings simply do not have the willpower to change and transform themselves unless assisted by irresistible grace. Pascal seems to be aware of this difficulty, as well. The quoted passage continues: “This will naturally make you believe and will stultify you . . . this way leads you to faith, let me tell you that it will lessen the passions which are your stumbling-blocks” (gutenberg.org). In other words, Pascal appears to be saying that passions can lead us astray. People who have no assurance of salvation can seek refuge in ascetic, anti-hedonist practices. They can only read indirect signs of their election, and they hope that one such sign is constituted by their virtuous behavior achieved through rigorous “warfare against the flesh.”

In the film, this topic is raised at dinner. Ironically, Vidal, who is an atheist, likes Pascal, while religious Jean-Louis is put off by his asceticism. He explains that, having lived in Clermont-Ferrand, Pascal has certainly drunk its excellent Chanturgue wine, but, according to the memoirs of his sister, he never praised it, nor did he ever notice what he ate, unlike Jean-Louis himself, who loves good food and drink and, in general, enjoys both the sensual and intellectual dimensions of life. But even intellectual pursuits can be the devil’s snare, according to the extreme ascetic ethos of Jansenism. At the end of his life, Pascal, the great mathematician, rejected mathematics itself as yet another worldly temptation, a useless intellectual diversion that needlessly excites passions.

And last but not least there is the question of whether we should, or can, choose at all. How is a wager possible within the constraints of a predestinarian doctrine? Must one choose? Why must one choose? Is the very notion of choice not a contradiction? Yet Pascal’s predestinarianism seems to convolute into a conviction that it is the wager itself that is not optional, not a choice. You cannot not choose, as he states in Pensees: “Yes; but you must wager. It is not optional. You are embarked. You are in the game. Which will you choose then?” Vidal quotes a similar passage: “If there are not infinite chances of losing compared to winning, do not hesitate. Stake it all. You are obliged to play. So renounce reason if you value your life.” The latter passage is reminiscent of God’s injunction to choose life, issued in Deuteronomy 30:19: “I call heaven and earth to record this day against you, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live.” In not being able or allowed to avoid choice, we cannot escape the givenness of our original spiritual condition. Our situation is such that we are always already launched into “the game” of moral choices and must therefore choose.

Pascal’s philosophical formulation of choice underscores the very issue of whether Jean-Louis is capable or incapable of moral choice, which is central to the film. Jean-Louis himself would certainly like to avoid or postpone choice. At the very least, he would like to deny its enormity. As Maud needles him about his being a “shame-faced Christian” who refuses to take responsibility for his actions, he grows irritated. “I thought every Christian was to aspire to sainthood,” says Maud. Jean-Louis answers that he cannot be a saint. Not everyone could be a saint, and he is apparently among those who cannot aspire to sainthood. He acknowledges his spiritual mediocrity and his “halfheartedness,” qualifying it by saying, “I am a man of the times, and religion acknowledges the times.”

Critics such as T. Jefferson Kline and Glen W. Norton have pointed out and debated the meaning of the visual effect of light behind Jean-Louis’s head as he is saying that he must have fallen into a snare of the devil, otherwise he would be a saint—adding that he cannot be a saint. Right before this admission, Jean-Louis is standing next to a painting of a glowing circle, which, in the idiom of religious iconography, reminds us of a halo over a saint’s head. But as the protagonist steps in front of the picture during his disavowal of sainthood, his head, instead of “filling” the empty halo, becomes misaligned with the source of light behind it. The halo does not “fit.” Whether this witty touch serves as an ironic underscoring of Jean-Louis’s failure at sainthood, according to the first critic, or a commentary on the paradoxical status of sainthood’s “impossible possibility” (25), according to the second one—in other words, whether it is ironic or in earnest, the misalignment does illuminate an underlying conflict of a double-bind character that every Christian has to face.

As lived experience, moral choice is central to the daily struggle of a Christian. Jean-Louis, for example, likes women, and has had several extramarital, albeit long-term and monogamous, affairs. How then will he be judged? Has he forfeited his eternal life? To justify his life and his choices, he has articulated two self-serving theories. One of them is that a Christian is judged not on one deed but cumulatively, on his entire life, with its preponderance, hopefully, of the good over the bad. His other theory is the so called “predestination” of luck. God or fate have been easy on him, as he explains to Vidal and Maud, and later to Françoise. He never had to face a temptation that was strong enough and would lead to a more serious sin than sins of indulgence. Therefore his moral choices have not required too much effort from him so far.

The various double-bind aspects of the wager encapsulate the paradoxical and transcendent nature of representation. An ultimate kind of wager is a wager with God himself, which is guaranteed by God and which challenges God, at the same time. It is a paradigm for all choice, because every act of decision takes place on the scene of representation vis-à-vis a symbolic central authority invested with transcendent attributes. Entering into this wager requires the mathematics of hope (mathematical expectation is l’espérance mathématique), negotiations of faith, and self-election into sainthood.

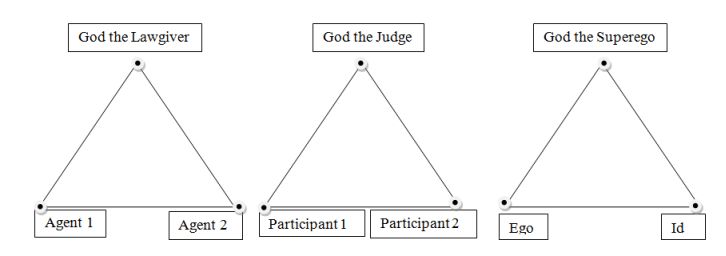

The three aspects of a wager—mathematical expectation, faith, and self-mastery—can be represented by three mimetic triangles, where the position of the sacred apex is occupied, respectively, by God-the-lawgiver, God-the-judge, and God-the-superego. This is based on the triple nature of transcendence—a) the unreachable (evolved from detached cognition), b) the other (the theory of mind), and c) the center (joint attention) (see my article in Anthropoetics, 15, 2, “Three Gaps of Representation / Three Meanings of Transcendence”). While each triangle focuses on one specific type of transcendence, it incorporates all three types of transcendence, since all three are inextricably interrelated. This point is made by Heidegger in The Metaphysical Foundations of Logic, when he compares and contrasts theological vs. epistemological transcendence (which correspond to the unreachable and unknowable transcendences, respectively). Heidegger notes that the two types of transcendence cannot be considered separately. He explains that as soon as we resort to the idea of the Other (epistemological transcendence), it forces us to think of an Absolute Other (with the Absolute evoking the theological meaning of transcendence).

Now both conceptions of transcendence, the epistemological and the theological, can be conjoined—something that has always happened and always recurs. For once the epistemological conception of transcendence is granted, whether expressly or implicitly, then a being is posited outside the subject, and it stands over against the latter. Among the beings posited opposite, however , is something which towers above everything, the cause of all. It is thus something over against [the subject] and something which transcends all conditioned beings over against [the subject]. (162)

I will now develop Heidegger’s analysis further, extrapolating it to make a similar argument for the third transcendence, which differentiates the center from the periphery. The reason I am expressing the transcendent relationships as triangles is because the triangle is the minimal configuration representing participants on the scene of representation.

Thus the first triangle expresses the first type of transcendence, that of detached cognition, which relates to calculation and reasoning based on causal chains. The rational aspect of Pascal’s wager involves the calculation of probabilities and mathematical expectations, which is connected to the first transcendence. Probabilities rely on stochastic laws. We cannot calculate a frequency of an event unless we can be assured of its regularity through some kind of a transcendent law. The central position in the triangle is occupied by God the lawgiver, who guarantees lawful regularities. The first position at the base of the triangle, that of Agent 1, represents myself, who needs to calculate probabilities, and who is also subject to lawful regularities. The second position represents the other, either human or a personified force of nature, who must also obey law in order to make it possible for me to calculate probabilities.

This cooperative mode of behavior (Agent 1 and Agent 2 cooperating with the law-giving center) can be represented through an orchestra paradigm: the center is occupied by the conductor, while the various members of the orchestra collaborate with the act of musical performance from their peripheral positions. Even though the transcendence I am focusing on is that of detached cognition, the other senses of transcendence, as per Heidegger, are also invoked. For example, the differentiated nature of this configuration, where God-the-Lawgiver occupies the central position, comes from the third sense of transcendence, while the other, who has a mind of his own but who must, nonetheless, cooperate and obey the law, is conjured up by the second transcendence. It is only by invoking all three types of transcendence that the idea of the laws of nature could be articulated.

The interaction of the three transcendences can be seen even more clearly when calculating probabilities. While deterministic laws of nature have to fire every single time, the stochastic laws are not equally reliable. If a certain action of mine does not guarantee a 100% certainty of success, making a decision in its favor involves the philosophical problem of counterfactuals with its paradoxical logic. If the plane I am on malfunctions and is hurtling toward the ground, would thinking about the statistical safety of air travel soothe me at that moment? What would it matter that my chance of arriving safely is 99.9%, as long as I fall in the remaining 0.1%? In some important respect, the domain of calculation and the domain of actual experience do not intersect.

And yet I make real-life choices, deliberately selecting situations that are not 100% safe. What am I thinking? According to the above model, I personify the distribution of probabilities as the first triangle. High probability is personalized by me, interpreted as God who has taken my side and has subdued the other (a looming catastrophe?) to prevent him from interfering. I suggest that we tend to personify probabilities in this fashion whether or not we are animists, conventional believers, or atheists, and whether or not we do it consciously, semi-consciously, or unconsciously. Any risk-taking decision arrogates to itself the benevolent God’s protection and the compliance of other actors on the scene of representation. Even the language of probabilities reflects this optimistic belief that God is on our side. When we speak of mathematical expectation or mathematical hope, we no longer mean the indifferent law-giving God but a concerned, providential God.

But the other side of God’s divine superintendence expresses the double bind, associated with this triangle, the double bind of freedom. Namely, if God governs the behavior of others, he must also be governing my own behavior. It is because God is in charge as the law-giver that it is possible for me to make future plans based on calculations, according to my capacity for detached cognition, and thus exercise my freedom. On the other hand, if I am also governed by divine law, then I am not a free agent, after all. Thus I am both free and not free.

The second triangle foregrounds the second transcendence, which represents the mystery and the ultimately unknowable nature of another mind, amounting to the problematic of trust. The model of the wager can also be seen a representation of the problem of trust/faith, which is the linchpin of all kinds of exchanges and contracts. By taking up a wager, I enter into a free contract with another participant on the scene of the market. How can I be certain that the other participant will hold up his end of the bargain? Do I place my trust in him implicitly or must I secure a central authoritative figure as the adjudicator? What underwrites my conscience is God-the-adjudicator, who is at the head of the second triangle, which represents the contractual nature of the wager.

But who is the second participant of this triangle? It is also God, with whom I conduct a wager. This dual role of God as both the judge and the participant testifies to the double-bind of faith, which has to do with an undecidability between faith as a performative act and faith as implicit trust. Placing my trust in the one with whom I conduct a transaction, as a limiting case of the exchange model, underscores the groundlessness of all grounding. Declaring my faith entails thus an oscillation between aligning myself with the center, which represents my conscience and is not in need of bargains, on the one hand, and fulfilling my part of the wager (a promise of good Christian conduct) on the periphery in deference to God-the-judge, on the other.

As in the first case, the focus on the second transcendence admits the interaction with the other two types of transcendence. Firstly, in order to set up the conditions for a wager, some antecedent calculations need to be performed, which necessitate the thinking-ahead of detached cognition, the first type of transcendence. In addition, the idea of centrality has already been invoked, which is that of the third, mimetic type of transcendence. In itself, the theory of mind, which underlies the second transcendence, does not require a third, mediating, member. But as soon as one posits two subjects opposite each other, the adjudicating center is brought into being.

The same reasoning holds for the third mimetic triangle, which focuses on the act of self-mastery—the ability to give up sensual pleasures and take control of amorous impulses in order to choose the life of a saint. To represent the dilemma of self-mastery, I choose Freud’s conceptualization of consciousness divided into the three compartments of the ego, id, and superego, because it seems to me a very apt representation of the problematic of self-mastery. The id is the animal part of us, which demands immediate satisfaction. The superego is the moral aspect of the psyche, which personifies societal prohibitions. It is the seat of moral consciousness, which prohibits satisfaction. The ego is the “self” of the subject, which is caught between the desires and constraints created by the id and superego.

Insofar as the ego employs the so-called “reality principle” in order to calculate the best ways of satisfying the id’s desires without committing grave social transgressions that would affront the superego, it avails itself of the first transcendence, because it is the first transcendence that deals with calculations and advanced planning. And insofar as it divides itself into three “persons” that are involved in negotiations and conflicts, it can be said to resort to the second transcendence, that which is invoked to describe our dealings with individual, unpredictable consciousnesses.

The paradox that this configuration embodies is that of the double-bind of mastery. What this refers to is the fact that the self cannot represent itself as fully masterful. If the ego takes the upper hand over the id, it is the superego, which emerges victorious, as the faculty which forced the ego to suppress the id’s desires. In the opposite case, when the id succeeds in pushing through its demands, it is the ego again that fails in its exercise of control.

In the last analysis, the superego is the place-holder for the voice of conscience, which calls us to choose faith. (In Heidegger, the faculty of summoning is also integrated into his analysis of subjectivity. The connotations of passivity and submissiveness in the word subject have arisen out of this interactive aspect of consciousness. Subjecthood, in other words, involves being subject to an occasional call of conscience which enjoins the self to engage in authentic action). Responding to the call to faith voluntarily, in a mood of agreeable inclination, almost anticipating it before it is issued, is a gesture of sovereignty and self-ownership. Such a response constitutes a genuine action—an act of accession to the center in the self-elected role of saint.

The three mimetic triangles combine, separate, and superimpose over each other, creating the contradictory configurations of action vs. suspension of action, inclusion vs. exclusion, trust vs. mistrust, free will vs. constraint, reluctance vs. compulsion of choice, etc., all of which epitomize the problematic of wagering and are explained by the originary paradox of the sign, expressive of the fundamentally untenable situation of human desire being structurally predicated on its impossibility of realization.

The oscillation between an imaginary prolongation of the acquisitive gesture toward the central object and the desisting gesture of recoil from the sacred center or “the oscillation between the contemplation of the referent as formally designated by the sign . . . and the imaginary contemplation of the referent alone as content” creates the paradoxical structure of the sign which lies at the heart of representation.

The back-and-forth movement gives rise to the phenomenon of dual perception that differentiates between two states. I would like to refer to these two states as acquisitive vs. reverential. In the reverential state, all participants on the scene of representation step away from the central object in the spirit of veneration that recognizes its sacred status. This state expresses the collective consciousness of the originary scene. In the acquisitive frame of mind, the participant perceives the distance between himself and the center as theoretically breachable and can imagine himself acceding to it. The other participant on the scene has become his rival, and the original participant envisions himself as excluded from the scene by an imaginary collusion between his rival and the center, similarly to the way Cain felt excluded by a perceived fellowship between Abel and God.

In My Night at Maud’s, this oscillation is captured by the theme of proper vs. improper centering. The improper centering is created by the mimetic triangle between Maud, Vidal, and Jean-Louis. Even though Jean-Louis resolves that he will find and marry Françoise, who is still a stranger at this point, he almost succumbs to the temptation of becoming intimate with Maud. From the very start, there is a certain suggestiveness to their introduction. By adumbrating Jean-Louis and Maud’s meeting in the way he does, Vidal plants a seed of anticipation in his friend’s head. He stops just short of suggesting that something might happen between these two. But after he notices that she is flirting with Jean-Louis, he appears to have had a change of heart, becoming himself flirtatious with her and acting in an affectionately physical way. Jean-Louis and Vidal’s triangular attention is focused on Maud as an improper center.

The key detail is that Maud does not have a separate bedroom. She sleeps in her living-room, and her bed is prominently displayed there. At some point late in the evening, Maud says that she is tired but not sleepy, and would like to go to bed, but would also like the men to stay and chat with her, so pretending this to be a “salon from the olden days.”

She leaves and comes back, dressed in an ostensibly simple but sexily short nightgown, and climbs into her bed. Her bed thus becomes a center stage on which the desiring gazes of the protagonists have converged—an improper center stage, insofar as it performs an illegitimate inversion between private and public spaces. The bed, an intimate piece of furniture, with its occupant wearing an intimate article of clothing, do not belong in the living room.

This scene is later mirrored by a symmetrical scene in which the protagonist walks into Françoise’s bedroom. Françoise’s posture, facial expression, and even the glimpse of her fussy nightgown leave no doubt that, in this case, he has intruded into a deeply private space.

It is the impropriety of Maud’s bed as the center that has created the momentum of mimetic contagion. Vidal grows sullen and starts drinking, and finally leaves abruptly. He seemingly jokingly pushes Jean-Louis back into an armchair and orders him to stay, as if usurping the central God-like position of throwing the other two together.

Maud’s interpretation of his taking leave is that it was “pure bravado.” According to her spin on things, she is the one who has rejected Vidal, who had been in love with her. As she is talking about his rival, Jean-Louis, who has a moment ago been trying to convince her of his conversion to celibacy, gets up from his seat and sits on her bed. As he responds, he is leaning toward her and speaking in a very seductive way. She stops him by switching the conversation to a more impersonal topic.

In the end, Jean-Louis crosses over the barrier to the mimetic center when he accepts Maud’s invitation to sleep next to her. In the scene that is reproduced on some posters and DVD covers of the film, Jean-Louis is depicted lying next to Maud in bed. Jean-Louis wraps himself pointedly in an individual blanket and tries to face away from Maud. Yet on awakening, he almost succumbs to temptation.

An almost complete inversion of this scheme occurs in the church scene with Françoise. After the protagonist spends the night in Françoise’s otherwise deserted dormitory, she realizes that she has not mistaken herself in trusting this complete stranger. In the morning, she is almost giddy with happiness. Jean-Louis has passed the test in her eyes. This is the first Sunday after Christmas, and they go to church together. Now we have the third, and the most important, church scene in the film. In each scene, we are shown the same priest, perfectly centered. This is especially apparent in the first scene, when we are shown the priest conducting the ritual of the sacrament while being in the perfect center not just of the film frame but of the whole interior architectural ensemble, where he appears properly in his place, properly centered and thus invested with the proper authority of God’s representative that induces respectful distance from the congregation.

In the final church scene, we just see a close-up of him (also centered) giving a sermon on being called to sainthood. Both Jean-Louis and Françoise are in a state of rapt attention. They are listening not as two separate people but in an attuned awareness of each other. Their body language reproduces the scene of joint attention, the third-order attention that is one of the most important evolutionary milestones on the way to language. It is this reciprocal attention that lays the foundation for the verticality of language (allowing the participant to switch attention between the other participant and the central object) and the differentiation between the center and the periphery. Jean-Louis and Françoise seem to communicate through subtle body-language cues. In a complete reversal of the bed scene, it is the priest now who is in the middle, with the two protagonists on the periphery, and, instead of being turned away from each other, they are slightly turned toward each other, listening to the priest as one unit.

What is the significance of the final sermon? The priest says: Christianity is not a moral code. It is a way of life, which is an adventure in sanctity. The sermon functions as an invitation—an invitation to be admitted to the center, by becoming a saint. It is an invitation that cannot be refused. The priest calls this path “a linking, a progression” that carries one along to holiness. But this progression is not the same as the progression of a mimetic contagion. It is the irresistible progression of faith, the irresistible working of grace. And the admittance to the center is not effected through an acquisitive gesture that excludes the other and obliterates the difference between center and periphery. It is brought about via an act of absolute inclusion that René Girard describes as an act of Imitatio Christi—imitating Christ not so much in the sense of imitating his good works but rather in the sense of imitating his non-acquisitive desire to resemble God the Father. This act of inclusion both preserves the worshipful distance to the sacred center and, paradoxically, invites the faithful to accede to it.

My claim is that the undeclinable and irresistible invitation to become a saint is a way out of the wager’s economy of calculation (as quoted above, what Jean-Louis does not like about Pascal’s wager is its economy of exchange) into sainthood’s logic of singularity. Despite denying Maud’s earlier claim that “every Christian is to aspire to sainthood,” Jean-Louis is not fully honest with himself. It is his fear and reluctance that are speaking. His friends too challenge him on his small prevarications. “You stake nothing, you give up nothing,” as Vidal chides Jean-Louis. Jean-Louis postpones and delays because becoming a saint is an act of sheer audacity. Even the priest says that one has to be insane to choose this path.

In linguistic terms, it is the audacity of arrogating the subject position, of speaking the “I.” It is only the subject that can tell a truly original narrative, breaking free of the mimetic economy of contagion. Staying on the periphery leaves one forever entangled in imitating already existing narratives. One of the striking images of this film, returning under several guises, is that of pursuing the path of desire and not being able to stop. In one of the striking early scenes, Jean-Louis is shown chasing Françoise in his car through the narrow winding streets of Clermont-Ferrand as she weaves through traffic on her scooter and eventually disappears. A similar idea is evoked by recurring allusions to slippery roads and losing control while driving, such as when Maud asks Jean-Louis to stay. A relevant and fascinating sequence in this respect is the one where Jean-Louis is looking for matches in the spare dormitory room of Françoise’s house where he has been placed. He really must smoke, but the matches are in Françoise’s room. He does not speak, but the viewer can literally read his thoughts, which are almost palpable, in the way he hesitantly approaches her room. “If I knock on her door, she will think that I have some designs on her. She will become scared, thinking that she has made a mistake, inviting a complete stranger to sleep under her roof. And yet I really want to smoke.” This I find to be an especially vivid example of how anticipations are formed mimetically out of a finite repertoire of already familiar narratives.

In contrast to that, only someone in the position of a saint can tell a truly new narrative. Genuine newness, according to the priest, is the real meaning of Christmas. In the sermon that he gives on Christmas eve, he tells his congregation that the joy he wishes them is the joy of newness. It is not the nostalgic joy of childhood memories or pious adherence to traditions. It is a celebration of new beginnings, a celebration not only of the birth of Christ but of our own rebirth. When in his last sermon, the priest refers to Christian life as an adventure, he means a truly new adventure, not one constructed according to old models but one that has never been told before. Becoming a saint involves the self-confidence of daring to tell a narrative for the very first time, but also a vulnerability of exposing yourself to the position of a scapegoat.

The final episode of the film proves that Jean-Louis has taken the priest’s sermon to heart. His allowing Françoise to think the worst about himself and Maud in order to make her feel less guilty is an act of true meekness, modeling itself on the lamb who takes away the sins of the world—the ultimate sacrificial position.

The centering of the subject position is achieved through a self-grounding narrative. In Rohmer’s film, this grounding is effected through the device of epiphany. In one of the early scenes, the protagonist tells us that he has just had a sudden insight about marrying Françoise. Yet at this moment he does not yet know the name of the woman he has fallen in love with. This signals to the viewer that the scene should be viewed from the perspective of the narrative past. The narrator already knows what has taken place. But his alter-ego hasn’t lived through this yet. It is clear that the epiphanic realization is a narrative post-construction. But this is exactly how epiphanies ground choice. They are convoluted paradoxical structures that set up the dual perspective of prospective and retroactive movement. (See my article, “The Limit of Explanation: Following the “Why” to its Epistemological Terminus,” Anthropoetics 10, 1.) A possibility is materialized by converging the past and the future into one point and presenting it as something that has already happened. If something has already happened then the possibility under consideration was the only viable possibility to begin with.

But there is a visual aspect to this epiphany that acts at cross purposes with the semantic one. The narrative voice says “On that Monday, December the 21st, I suddenly knew, without a doubt, that Françoise would be my wife.” “Suddenly, without a doubt” is the rendering of the French “brusque, precis, definitive,”—words that clearly mark a specific moment. Yet nothing is happening visually to punctuate the meaning of the voice-over narrative. The camera is showing us the nondescript view of a curb as Jean-Louis’s car speeds along a dark street. It is only the next second that Françoise’s scooter appears suddenly alongside it. The visual misalignment, reminiscent of the other ironical misalignment—that of Jean-Louis’s head and the halo—subverts the authoritative status of the epiphany, reminding us that it is perhaps impossible, after all, to arrogate to oneself the center.

Works Cited

Bedouelle, Guy. “Eric Rohmer on Nature and Grace.” New Blackfriars. 74.872 (June 1993): 301–306. Print.

Ennis, Tom. “Textual Interplay: The Case of Rohmer’s Ma nuit chez Maud and Conte d’hiver.” French Cultural Studies 7 (1996): 309-319. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. On Metapsychology: The Theory of Psychoanalysis. Vol. 11. Penguin Books, 1964. Print.

Gans, Eric. The End of Culture: Toward a Generative Anthropology. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1985. Print.

—. Originary Thinking: Elements of Generative Anthropology. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1993. Print.

—. Signs of Paradox: Irony, Resentment, and Other Mimetic Structures. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1997. Print.

—. The Scenic Imagination: Originary Thinking from Hobbes to the Present Day. Stanford, California: Stanford California Press, 2008. Print.

Girard, René. Deceit, Desire, and the Novel. Trans. Yvonne Freccero. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1965. Print.

—. I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. Trans. James G. Williams. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2001. Print.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. Trans. Joan Stambaugh. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996. Print.

—. The Metaphysical Foundations of Logic. Trans. Michael Heim. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992. Print.

Kline, T. Jefferson. Screening the Text: Intertextuality in New Wave French Cinema. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1992. Print.

Lai, Wai-ting, Thomas. “Wagering Love between Desire and Discipline : A Study of Sexual Power in Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales.” The HKU Scholars Hub. 2011. The University of Hong Kong. Web. 10 Apr. 2012. href=”http://hdl.handle.net/10722/144143″>http://hdl.handle.net/10722/144143

Ludwigs, Marina. “The Limit of Explanation: Following the “Why” to its Epistemological Terminus.” Anthropoetics 10.1 (2004): n. pag. Web. 10 Apr. 2012. http://anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap1001/explanation.htm

Ludwigs, Marina. “Three Gaps of Representation / Three Meanings of Transcendence.” Anthropoetics 15.2 (2010): n. pag. Web. 10 Apr. 2012. http://anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap1502/1502Ludwigs.htm

Norton, Glen, W. “Moral Perfectionism in Eric Rohmer’s Ma nuit chez Maud.” Studies in French Cinema. 9.1 (2009): 25-36. Print.